The shape of medical device surfaces can become a powerful ally in preventing infections. Catheters, stents, and implants can in fact provide bacteria with ideal surfaces on which to adhere and proliferate, promoting the formation of biofilms – bacterial communities with characteristics that protect microorganisms, making infections persistent and difficult to treat with antibiotics. Hospital-associated infections are estimated to exceed 50 million cases worldwide each year, with more than 60% attributed to biofilm-related infections. It is therefore crucial to study the surfaces of these devices in order to minimize bacterial colonization and prevent harmful consequences for patients.

A study published in Nature Communications shows how surface geometry can effectively be exploited to hinder bacterial adhesion. The research was conducted by Roberto Rusconi, head of the Applied Physics, Biophysics and Microfluidics Unit at Humanitas Research Hospital and associate professor of Applied Physics at Humanitas University, together with Luca Pellegrino, postdoctoral researcher in the same laboratory.

Until now, the prevailing assumption was that biofilm formation and infections associated with medical devices depended mainly on material chemistry or the use of antimicrobial coatings. Data emerging from this study add microscopic surface geometry to the features that can be leveraged to prevent bacterial colonization. The research focused on corrugated surfaces created in the laboratory, but its conclusions are relevant for all devices in contact with bodily fluids.

A shift in perspective, from chemistry to physics, inspired by sharks and dragonflies

Biofilm formation on catheters and other implants exposed to a continuous flow of bodily fluids is one of the main causes of persistent, antibiotic-resistant infections and clinical complications. To address this problem, the researchers adopted an approach different from traditional methods based on chemical modifications or antimicrobials, instead focusing on a purely physical strategy. Inspiration came from the natural world: dragonflies and sharks have anti-adhesive surfaces thanks to the way they are shaped, not because of specific chemical substances.

“If a surface does not offer a stable foothold, bacteria are swept away by the flow of water, urine, or other bodily fluids in which the devices are immersed, before they can colonize it,” explains Roberto Rusconi. “We discovered that geometry can make a big difference. Carefully designed microscopic wrinkles and folds create a kind of mechanical barrier that prevents bacteria from attaching. It is a completely physical mechanism, based on fluid dynamics and the behavior of microorganisms.”

Using PDMS, a silicone polymer similar to the material used in many medical devices, the team created surfaces with microscopic corrugations generated through controlled mechanical stretching and surface treatments. These structures form spontaneously through a physical phenomenon known as buckling instability, similar to the wrinkles that appear on skin when it is compressed.

The corrugated surfaces were tested by reproducing the flow conditions to which real medical devices implanted in the human body are typically exposed, allowing researchers to observe how bacteria interact with surfaces that are closer to clinical reality than traditional static tests. In addition to constant flows, the researchers also tested intermittent flow conditions, in which fluid velocity varies over time, simulating physiological situations such as urinary flow.

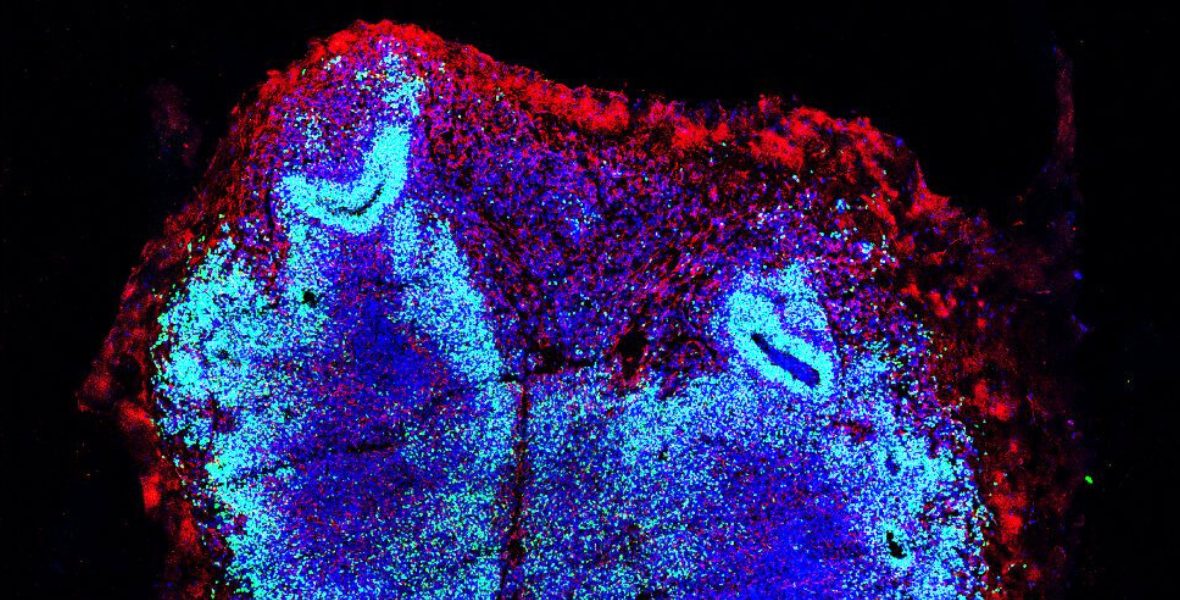

Imaging at millionths of a millimeter, thanks to CLEM

The shape, height, and size of the ripples on the surfaces created by Prof. Rusconi’s team needed to be observed with precision. To this end, Francesco Mantegazza from the University of Milan–Bicocca was first involved to carry out the initial measurements using Atomic Force Microscopy. Subsequently, the newly established CLEM Laboratory at Humanitas University, led by Edoardo D’Imprima, came into play. This laboratory combines optical fluorescence microscopy – used to observe dynamic events in tissues – with electron microscopy, which provides nanometer-scale resolution for analyzing the structure of cellular components.

This made it possible to integrate the dynamic observation of bacteria with ultra-high-resolution images of the surfaces: one millionth of a millimeter, a resolution that allowed the study of material and biofilm in ways previously unattainable, to determine which shape and spacing of waves was most effective in preventing bacterial proliferation.

When geometry hinders bacteria

The results showed that certain fold configurations reduce bacterial adhesion by more than 90% and hinder biofilm formation, particularly with wrinkles of about five micrometers (five millionths of a meter). This effect was observed, under varying flow conditions, with two bacteria of major clinical relevance, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus, responsible for a significant proportion of biofilm-associated hospital-acquired infections on medical devices such as catheters, stents, and endotracheal tubes.

The study also highlighted how the orientation of the corrugations influences the effectiveness of the system: wrinkles perpendicular to the flow allow for bacteria removal much more rapidly than folds aligned parallel to it. This result was further confirmed by numerical simulations describing the interaction between flow, surface topography, and microbial behavior, as well as by comparisons between bacteria with modified or unmodified motility capabilities.

By keeping surface chemistry constant, the researchers confirmed that the observed effect is due exclusively to geometry. “Taken together, these data point to a promising, drug-free strategy for designing safer medical devices,” explains Luca Pellegrino. “This discovery paves the way for new designs of catheters, stents, and implants capable of drastically reducing the risk of infections while avoiding antibiotic resistance.”

Corrugated surfaces inspired by physical and biological principles could therefore represent a long-lasting alternative to traditional antimicrobial coatings, helping to reduce healthcare-associated infections.